1. High selectivity is normal, especially as we get older

When you enter the post-20’s dating world, your life experience has shaped your preferences. You’ve likely developed clear ideas of what you want in a partner, both in terms of personality and compatibility.

- This means it’s natural to not feel interested in most people you date.

- Selectivity isn’t a problem—it often reflects self-knowledge and maturity.

2. Same-sex dating dynamics can be tricky

- In male same-sex dating, especially in places like Sydney, there can be a stronger focus on physical attraction in initial meetings.

- That can make it harder to find someone you genuinely click with emotionally or mentally, because a lot of initial dating chemistry may feel superficial or performance-based.

3. Emotional vs. physical attraction

- Your emotional and intellectual connection becomes [more] key to your interest.

- You may feel attracted physically to some, but if the emotional or personality resonance isn’t there, you simply won’t want to continue. That’s perfectly normal.

4. Reciprocity matters a lot

- Humans are wired for reciprocal interest: when it’s not returned, our brains often disengage emotionally to protect ourselves from disappointment.

- This can make dating feel discouraging because your standards and their feelings don’t always align.

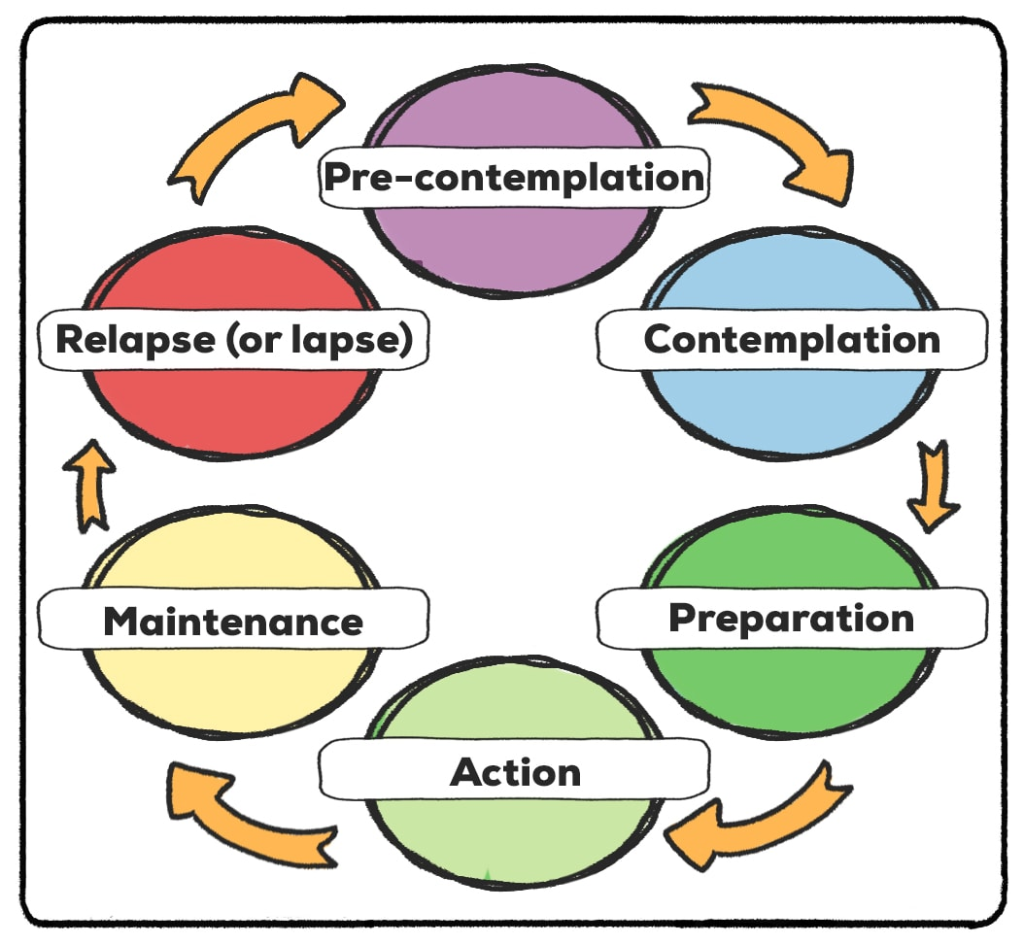

5. Psychological patterns that could be at play

- High self-awareness: You know what you want and won’t settle.

- Emotional caution: After multiple dates where interest isn’t reciprocated, your mind may naturally limit attachment until someone truly matches your criteria.

- Confirmation bias in dating: You notice quickly when someone isn’t “right,” which is good for avoiding poor matches—but can also make you feel like genuine connections are rare.

6. This is very common for mature adults dating

- Many people in their late 30s–40s experience the same thing.

- Your dating pool is smaller because you’re looking for someone with very specific qualities (age, personality, emotional intelligence, compatibility).

Practical advice for dating in this context

a. Broaden [wisely] your dating strategies

- While selectivity is good, small adjustments in mindset can increase your chances:

- Look beyond initial “type” indicators and give people a bit more time to reveal personality.

- Join social groups or interest-based communities (sports clubs, arts, volunteering, LGBTQ+ meetups). Often chemistry develops in shared activity contexts rather than first-date settings.

b. Focus on quality interactions

- Instead of increasing quantity, increase meaningfulness: fewer, more intentional dates with people you have some natural overlap with (values, lifestyle, humor).

- Online apps can be helpful, but try to filter for shared interests or mutual values to save time and emotional energy.

c. Work on internal calibration

- Reflect on what triggers your strong attraction. Are there patterns (personality, energy, humor, confidence)?

- This helps to recognize potential even if it’s not immediately intense, and also helps articulate your preferences clearly to prospective dates.

d. Manage expectations

- It’s normal for the dating ratio (you like → they like) to be low, especially with high selectivity. Patience is key.

- Celebrate the small wins: every connection you explore, even if it doesn’t last, builds social and emotional insight.

e. Emotional self-care

- Rejection is part of the process and rarely personal—it’s more about compatibility.

- Maintain supportive friendships, hobbies, and self-affirmation to avoid over-investing emotionally in every date.

Mindset shift suggestion

Instead of thinking:

“There are very few people I want to see again, and they don’t feel the same way”

Try:

“I’m selective and I know what I want. Meeting the right person may take time, but each date helps me understand myself and my preferences more clearly.”

This subtle mindset shift reduces pressure and anxiety, while keeping your standards intact.