You attract what you are, not what you want. The Universe always balances itself out. Hence, Yin and Yang is everywhere we look and everywhere we cannot see.

Related Post

Self-sabotage is self-sabotaging. Why would anyone do this?Self-sabotage is self-sabotaging. Why would anyone do this?

As I always like to say, there are as many reasons why people self-sabotage as there are people. A common theme is to protect the self from failure, feeling things we don’t want to feel, and to control our experiences.

One of the hidden culprits behind self-sabotage is the need for perfection and control. Self-sabotage has a strange way of helping us maintain the illusion that if only we had put in more effort or had better circumstances, everything would have worked out as it should. Social psychologists call this counter-intuitive strategy of regulating self-esteem ‘self-handicapping.’ It’s very seductive to engage in self-sabotage because the hidden payoff is high. It’s often easier to be a perfect whole rather than a real part. It’s a short-term solution that sidesteps the more arduous but ultimately more fulfilling work of individuation and self-realization. It takes risk, patience, suffering, and ultimately wisdom to come to the place where you can let go of self-sabotage and learn how to be real.

Behaviour is said to be self-sabotaging when it creates problems in daily life and interferes with long-standing goals. The most common self-sabotaging behaviors include procrastination, self-medication with alcohol and other drugs, comfort eating, and forms of self-injury such as cutting.

Self-sabotage originates in the internal critic we all have, the side that has been internalized by the undermining and negative voices we’ve encountered in our lives. This critic and ‘internal sabotuer,’ functions to keep the person from risking being hurt, shamed, or traumatized in the ways they had been in the past. While it keeps the individual safe, it does so at a very high cost, foreclosing the possibility of new, creative, and three-dimensional experiences. Like an addiction, self-sabotage insidiously lulls and deludes us into thinking that it has the answer. In fact, it is the problem masquerading as the solution. Nothing stops self-sabotage faster in its tracks than shining this particular light on it. Consciousness is true power. We need to let go of our illusions of omnipotence and perfection and see that it is only when we are real and imperfect that we can create a true work of art. Then and only then we can enjoy the gifts of being Real.

– Michael Alcée, Ph.D., Relational therapist/ Clinical psychologistArt: Bawa Manjit, Acrobat

Fear and Love, with Tara BrachFear and Love, with Tara Brach

I strongly encourage viewers, readers, and interested friends to visit Tara’s website Tara Brach – Meditation, Psychologist, Author, Teacher. So much of what I consider to be true and helpful is the wisdom I have learned from Tara Brach, an American psychologist, author, and proponent of Buddhist meditation – but more than that, she is authentic, compassionate and honest.

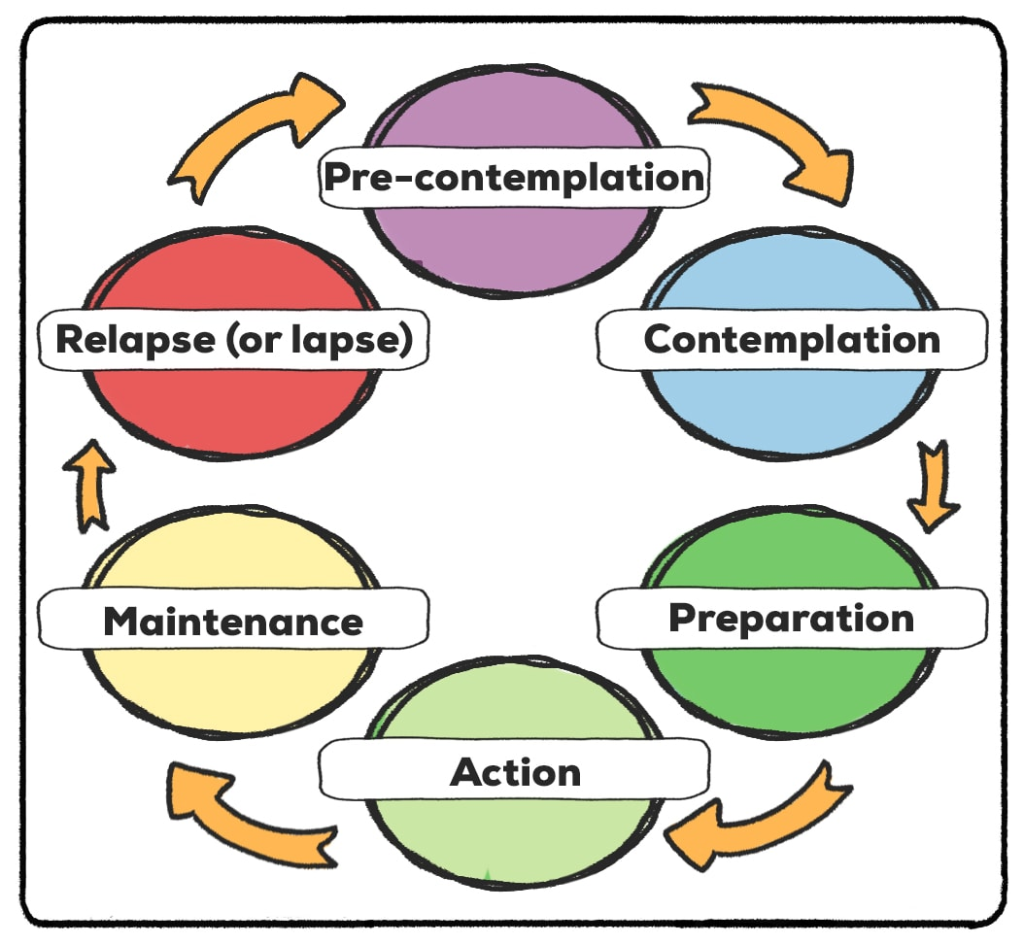

The stages of change modelThe stages of change model

‘The stages of change model’ was developed by Prochaska and DiClemente. Heard of them? It informs the development of brief and ongoing intervention strategies by providing a framework for what interventions/strategies are useful for particular individuals. Practitioners need an understanding of which ‘stage of change’ a person is in so that the most appropriate strategy for the individual client is selected.

There are five common stages within the Stages of Change model and a 6th known as “relapse”:

1. In the precontemplation stage, the person is either unaware of a problem that needs to be addressed OR aware of it but unwilling to change the problematic behaviour [or a behaviour they want to change. It does not always have to be labelled as “problematic”].

2. This is followed by a contemplation stage, characterized by ambivalence regarding the problem behaviour and in which the advantages and disadvantages of the behaviour, and of changing it, are evaluated, leading in many cases to decision-making.

3. In the preparation stage, a resolution to change is made, accompanied by a commitment to a plan of action. It is not uncommon for an individual to return to the contemplation stage or stay in the preparation stage for a while, for many reasons.

4. This plan is executed in the action stage, in which the individual engages in activities designed to bring change about and in coping with difficulties that arise.

5. If successful action is sustained, the person moves to the maintenance stage, in which an effort is made to consolidate the changes that have been made. Once these changes have been integrated into the lifestyle, the individual exits from the stages of change.

6. Relapse, however, is common, and it may take several journeys around the cycle of change, known as “recycling”, before change becomes permanent i.e., a lifestyle change; a sustainable change.

(Adapted from Heather & Honekopp, 2017)