What is meant by self-harm?

Self-harm is any behaviour that involves the deliberate causing of pain or injury to oneself without the intention to end your life. Self-harm can include behaviours such as cutting, burning or hitting oneself, binge-eating or starvation, or repeatedly putting oneself in dangerous situations. It can also involve abuse of drugs or alcohol, including overdosing on prescription medications. Self-harm is usually a response to distress, whether it be from mental illness, trauma, or psychological pain. Some people find that the physical pain of self-harm helps provide temporary relief from emotional pain (extract from Self harm (lifeline.org.au)).

People who engage in self-harm will profess that they have no intention of dying and that their self-harming behaviour is a coping strategy, however, there are incidents of accidental suicide. The act of self-harm can develop into an obsessive-compulsion experience which can be very difficult to stop, like addiction, without outside intervention. This can result in feelings of hopelessness and possible suicidal thinking. Like building a tolerance to a drug, when self-injury does not relieve the tension or help control negative thoughts and feelings, the person may injure themselves more severely or may start to believe they can no longer control their pain and may consider suicide.

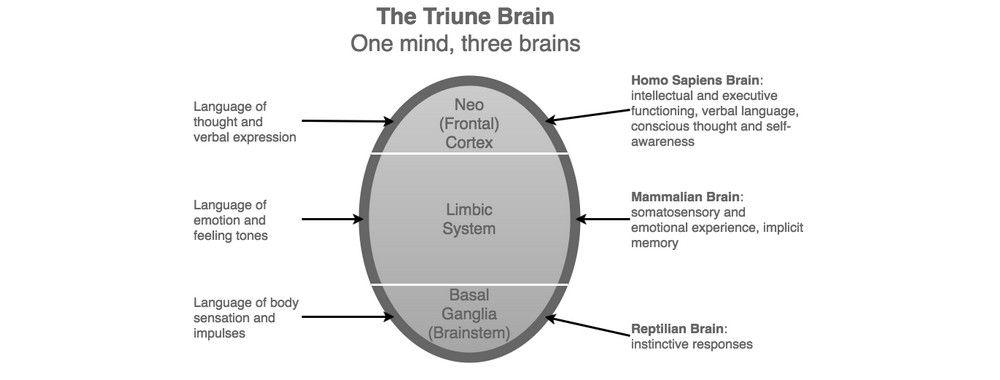

The following extract by Tracy Alderman Ph.D explains the physiological response to physical pain:

“Physiologically, endorphins are released when we are injured or stressed. Endorphins are neurotransmitters that act similarly to morphine and reduce the amount of pain we experience when we are hurt. Joggers often report experiencing a “runners high” when reaching a physically stressful period. This “high” is the physiological reaction to the release of endorphins – the masking of pain by a substance that mimics morphine. When people self-injure, the same process takes place. Endorphins are released which limit or block the amount of physical pain that’s experienced. Sometimes people who intentionally hurt themselves will even say that they felt a “rush” or “high” from the act. Given the role of endorphins, this makes perfect sense” (Oct 22, 2009).

Please click on the link for the full article Myths and Misconceptions of Self-Injury: Part II | Psychology Today Australia

The first step is to distinguish between self-harming and suicidal behaviour by paying attention to a person’s underlying motivation. When working with self-harming behaviour it is important to remember that this behaviour serves a purpose. In collaboration with the client, try to identify what problem self-harm solves for the client. For example, from the client’s perspective:

- To make me feel real (counteracts dissociation)

- To punish me (temporarily lessens guilt or shame)

- To stop me from feeling (when strong feelings are too dangerous)

- To mark the body (to show externally the internal scars)

- To let something bad out (symbolic way to try to get rid of shame, pain, etc.)

- To remember

- To keep from hurting someone else (to control my behaviour and my anger)

- To communicate (to let someone know how bad the pain is)

- To express anger indirectly (to punish someone without getting them angry at me)

- To reclaim control of the body (this time I’m in charge)

- To feel better

Tips for helping yourself in the moment

It can be hard for people who self-harm to stop it by themselves. That’s why it’s important to get further help if needed; however, the ideas below may be helpful to start relieving some distress:

- Intense exercise for 30 seconds, 30 second break, repeat, up to 15 minutes – Exercising intensely will help your body mitigate unpleasant energy that can sometimes be stored from strong emotions. Transfer this energy by running, walking at a fast pace, doing jumping jacks, etc. Exercise naturally releases endorphins which will help combat any negative emotions like anger, anxiety, or sadness.

- Delay — put off self-harming behaviours until you have spoken to someone.

- Distract — do some exercise, go for a walk, play a game, do something kind for yourself, play loud music or use positive coping strategies.

- Deep breathing — or other relaxation methods.

- Cool your body temperature – Cooler temperatures decrease your heart rate (which is usually faster when we are emotionally overwhelmed). You can either splash your face with cold water, take a cold (but not too cold) shower, or if the weather outside is chilly you can go outside for a walk. Another idea is to take an ice cube and hold it in your hand or rub your face with it.

- Listen to loud music

- Call someone you trust or one of the services available like LifeLine 13 11 14, MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78 and BeyondBlue 1300 22 4636 [see below].

- You could write an email to yourself to express your emotions, or journal your feelings, if that’s something that might be effective for you.

- Watch humorous Youtube clips

New, healthier coping strategies may not be as effective as the one you’re trying to replace so it may take practice. Bring lots of compassion to yourself, okay.

You may find that some of these strategies work in some situations but not others, or you may find that you need to use a combination of these. It’s important to find what works for you. Also, remember that these are not long-term solutions to self-harm but rather, useful short-term alternatives for relieving distress.