What we think about, we bring about.

Related Post

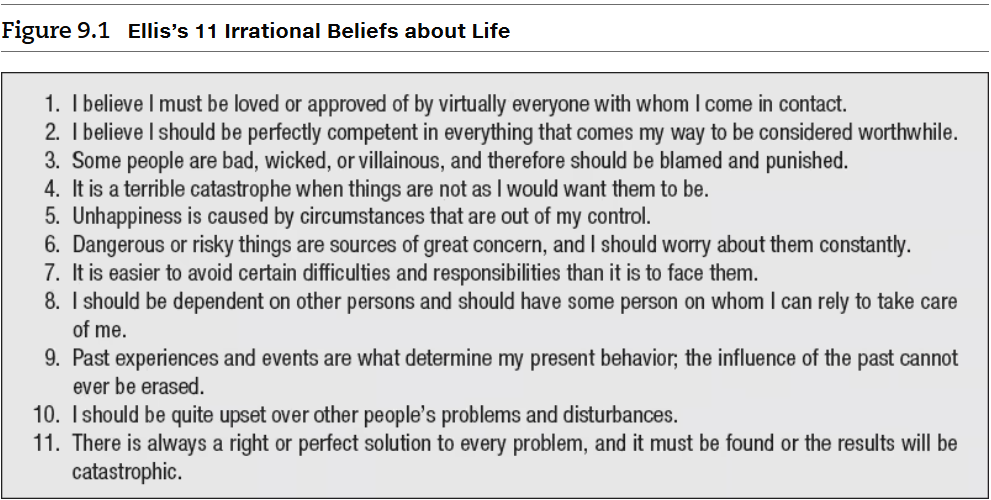

Albert Ellis’s “Irrational Belief’s about Life” and Self-stereotypingAlbert Ellis’s “Irrational Belief’s about Life” and Self-stereotyping

Albert Ellis, in his Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT), identified a number of dysfunctional beliefs that people often hold. Ellis intentionally adopts extreme views to emphasize how people often exaggerate their perspectives irrationally. He referred to this tendency as “awfulizing,” where we negatively overgeneralise situations. This behaviour can stem from a strong desire for certainty, causing us to perceive things in extreme terms rather than viewing them as part of a nuanced spectrum. Consequently, this leads to the formation of self-stereotypes.

A self-stereotype refers to the process of applying generalised beliefs or stereotypes about a group to oneself, especially when one identifies as part of that group. For instance, if someone belongs to a specific cultural or social group (gay men) and internalises the commonly held stereotypes about that group (partying and casual sex), they may unconsciously start viewing and behaving in ways that align with those generalisations.

AIPC (2021). Busting Common Myths About Anger. Issue 355 // Institute Inbrief. Retrieved June 17, 2021.AIPC (2021). Busting Common Myths About Anger. Issue 355 // Institute Inbrief. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

All human beings experience anger at least occasionally. It’s a natural emotion helping us recognise that we or someone or something we care about has been violated or treated badly. When we feel threatened or our goals are thwarted, anger is a coping mechanism that enables us to act decisively, especially in situations where there is little time to reason things out. It can motivate problem-solving, goal-achievement, and the removing of threats. It serves a protective function and is not always a problem (Lowth, 2018; Stosny, 2020; Zega, 2009).

But anger is a complex emotion, and all too often manifests maladaptively in clients’ lives, when they perceive excessive need for protection, protect the “wrong” things, or use anger to thwart their longer-term best interests. The result is problem anger.

Perhaps because it is so multi-faceted, misperceptions about anger abound, and the question arises: how shall we regard anger? How do we advise the client to think about it? Folk wisdom often would say that the best thing to do is just let it all out, but is it? Clients complain that they cannot control it, that the tendency to be easily angered is inherited, but again, is there evidence for that? Here are common myths people tend to hold about anger, and factual statements following them that you can use to clarify for the client why learning to deal with problem anger is time well spent.

Myth 1: “Anger is inherited.”

This is the client that may try to claim that their father was short-tempered and they have inherited that trait from him, so there is nothing they can do. Such a stance implies an attitude that the expression of anger is a fixed, unalterable set of behaviours. Research shows, however, that expression of anger is learned, so if we have – say, through exposure to aggressive influential others, such as parents – learned to be violent in our expressions, we can also learn healthier, more appropriate, pro-social ways of dealing with it.

Myth 2: “Anger and aggression are the same thing.”

Fact: Nope. Anger is a felt emotional state. Aggression is a behaviour, sometimes carried out in response to anger, but not the same as it. A person can be angry, yet use healthy methods of expression without resorting to violence, threats, or other aggression. Anger does not always lead to aggression. In fact, some experts claim that most daily anger is not followed by aggression. When it does result in aggression the “I3 Model” (pronounced “I cubed”) is deemed responsible. This suggests that aggression emerges as a function of three interacting factors, which all begin with “I”:

Instigation, an event which instils an urge to aggress as a result of, say, being addressed rudely or learning that one’s partner has had an affair (or a relatively “minor” event, such as being cut off in traffic);

Impellance, meaning a force that increases the urge to act in response to an instigating stimulus. These could be strong hormonal releases or a belief system which says that the instigating event should not be tolerated, or even a sociocultural norm which demands that instigating stimuli be responded to immediately and harshly (such as punching back someone who has hit you);

Inhibition, referring to forces that typically work to counter aggression, such as cultural norms, awareness of negative consequences, or perspective-taking or empathy (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2019).

Myth 3: “Other people make me angry.”

Fact: How often in common parlance do we say things like, “He made me so angry!” or “You make me so mad I could kill you!”? Even though we may occasionally speak about people causing emotions other than anger, it is far more frequent to hear such statements in regard to anger. We can choose whether or not we let someone else’s behaviour make us happy, sad, or something else, but we often think and talk about it as if anger is caused directly by others. With the undiscerning listener, an angry person thus gets to use anger as an excuse for unacceptable behaviour. Ultimately, it is not the other person’s behaviour that causes our anger, and in fact, it’s not even their intention, though that may influence our behaviour. Being precise, we must acknowledge that it is our interpretation of their intention, expressed in their behaviour/language, which is causative.

Myth 4: “I shouldn’t hold anger in; it’s better to let it out” (either by venting or catharsis).

Fact: If by “holding it in” someone means that they suppress anger, it’s true; ignoring it won’t make it go away and squashing it down is not a healthy choice. Neither, however, is venting. Blowing up in an aggressive tirade only fuels the fire, reinforcing the problem anger. Ditto the use of pillow-punching or other means of catharsis; this may come as a surprise to therapists trained a few years ago, when catharsis was an anger management technique in good standing. Now researchers have found that, even though we feel better in the moment after hitting something, our brain notices, subtly changing its wiring. Then the next time we are angry it softly whispers, “Hit something; you’ll feel better”. The time after that, the wiring is stronger in the brain towards a hitting catharsis, and the angry-brain-voice speaks a little louder. Continuing in this vein means that eventually, we could decide to hit something more alive than a pillow. Rather than either angry venting or catharsis is the use of skills to manage the angry impulse.

Myth 5: “Anger, aggression, and intimidation help me to earn respect and get what I want.”

Fact: People may be afraid of a bully, but they don’t respect those who cannot control themselves or deal with opposing viewpoints. Communicating respectfully is a far superior way to get (most) people to listen and accommodate one’s needs. While the momentary power that comes with successful intimidation may feel heady in the moment, it does not help build the healthy relationships that most people coming to counselling yearn to have.

Myth 6: Anger affects only a certain category of people.

Fact: Anger is a universal emotion that affects everyone. It does not discriminate against people of any particular age, nationality, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, or religion. It is tempting for some people in the educated middle classes to believe that anger is more prevalent among the poor, or those who are less educated or lacking in social skills. Reality does not bear this out, although the expressions of anger do vary among different social groups. Remember, anger is just an emotion, one which does not make people “good” or “bad” for having it.

Myth 7: “I can’t help myself. Anger isn’t something you can control.”

We don’t always get to control the situations of our lives, and some of them may trigger our anger. In fact, it’s also agreed by experts that we don’t (in the short-term) control whether we have angry feelings or not; they just come – although there are longer-term ways to work with clients that see them less easily provoked, and therefore less prone to have the experience of anger. What we do have the short-term choice to control is how we express that anger. Continuing in sessions with you (the therapist) for the purpose of learning how to better handle anger means having more choices of response, even in highly provocative situations.

Myth 8: “When I’m angry I will say what I really mean.”

Fact: This is rarely true. Uncontrolled angry expressions are more about gaining control of or hurting others, not saying what a person’s deepest truth is.

Myth 9: “By not saying what I’m thinking in the moment, I’m being dishonest and will be even angrier later.”

Fact: There is a strong pull to “speak our mind” when angry. But it is at this time that a person’s judgment is most severely flawed. To speak from anger is to allow the impulsive part of the brain to overrule the rational part. Better for relationships, career, and pretty much everything else to wait until that reasoning part can regain control.

Myth 10: “Men are angrier than women.”

Fact: The sexes experience the same amount of anger, says research; they just express it differently. Men often use aggressive tactics and expressions, whereas women (often constrained culturally) more frequently choose indirect means of expression, such as found in passive-aggressive tactics. This could mean getting back at someone by talking negatively about them or cutting them out of their lives (categories adapted from: Therapist Aid LLC, 2016; Segal & Smith, 2018; Morin, 2015; Morrow, n.d.; Better Relationships, 2021; Gallagher, 2001).

Thought for reflection

Anger has many facets to it, and we have introduced some information here that may seem either startling or counterintuitive. As you think back over the myths we just debunked, which aspect has surprised you the most? Do you have any sense of why that might be? One woman, for example, was very surprised to hear that “men are angrier than women” was only considered a myth; it turned out that in her family, women “never got angry” (we hypothesise that perhaps they were socialised to not show anger), and the men got angry all the time (perhaps more allowed in that woman’s family/culture). In what ways, if at all, might your views about anger have shaped how you behave? How you respond to others?

And here’s the ultimate question if you share this material with a client: what are their responses to the above questions? How might hearing these myths help them seek more adaptive ways to deal with problem anger?

The upcoming Mental Health Academy course, “Helping Clients Deal with Problem Anger” draws from numerous therapies and neuroscience to help clinicians and clients collaboratively create a program to address each client’s unique challenges with this universal human emotion.

References:

- Better Relationships. (2021). Common myths about anger. Anglicare Southern Queensland. Retrieved on 13 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Gallagher, E. (2001). Anger. eddiegallagher.com.au. Retrieved on 13 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Kassinove, H., & Tafrate, R.C. (2019). The practitioner’s guide to anger management: Customizable interventions, treatments, and tools for clients with problem anger. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

- Lowth, M. (2018). Anger management. Patient. Retrieved on 7 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Morin, A. (2015). 7 myths about anger and why they’re wrong. Psychology Today. Retrieved on 13 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Morrow, A. (n.d.). Anger myths. Stress and Anger Management Institute. Retrieved on 13 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Segal, J., & Smith, M. (2018). Anger management: Tips and techniques for getting anger under control. Helpguide.org. Retrieved on 9 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Stosny, S. (2020). Beyond anger management. Psychology Today. Retrieved on 9 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Therapist Aid, LLC. (2016). Anger warning signs. Therapist Aid LLC. Retrieved on 7 April, 2021, from: Website.

- Zega, K. (2009). Holistic Psychotherapy (159). Retrieved on 7 April, 2021, from: Website.