Dr Rangan Chatterjee chats with Dr Gabor Maté about his radical findings based on decades of work with patients. We’re currently living in a culture that doesn’t meet our human needs. Maté and Chatterjee delve into how our emotional stress can translate into physical chronic illnesses, and how loneliness and a lack of meaningful connection are on the rise, as are the rates of autoimmune disease and addiction.

Related Post

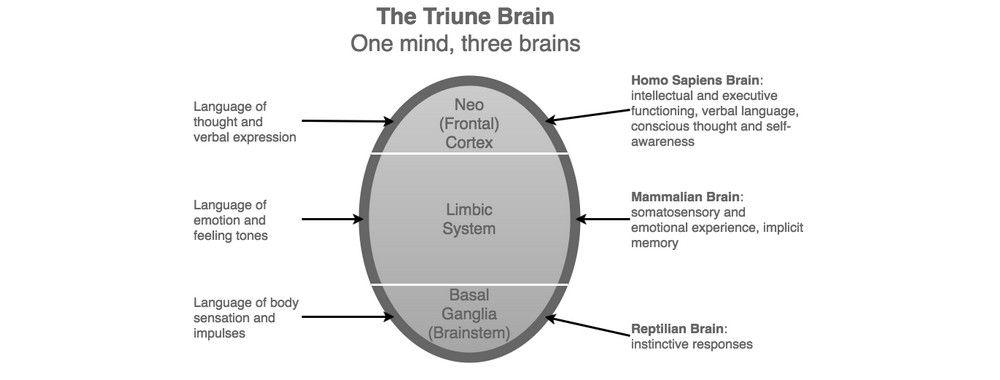

The ‘Triune Brain’ theory by Neuroscientist Paul MacLean — an evolutionary perspectiveThe ‘Triune Brain’ theory by Neuroscientist Paul MacLean — an evolutionary perspective

In the 1960s, American neuroscientist Paul MacLean formulated the ‘Triune Brain’ model, which is based on the division of the human brain into three distinct regions. MacLean’s model suggests the human brain is organized into a hierarchy, which itself is based on an evolutionary view of brain development. The three regions are as follows:

- Reptilian or Primal Brain (Basal Ganglia)

- Paleomammalian or Emotional Brain (Limbic System)

- Neomammalian or Rational Brain (Neocortex)

At the most basic level, the brainstem (Primal Brain) helps us identify familiar and unfamiliar things. Familiar things are usually seen as safe and preferable, while unfamiliar things are treated with suspicion until we have assessed them and the context in which they appear. For this reason, designers, advertisers, and anyone else involved in selling products tend to use familiarity as a means of evoking pleasant emotions.

Unhelpful Cognitions (thoughts) and DistortionsUnhelpful Cognitions (thoughts) and Distortions

Unhelpful Cognitions

Mental Filter: This thinking style involves a “filtering in” and “filtering out” process – a sort of “tunnel vision”, focusing on only one part of a situation and ignoring the rest. Usually this means looking at the negative parts of a situation and forgetting the positive parts, and the whole picture is coloured by what may be a single negative detail.

Jumping to Conclusions: We jump to conclusions when we assume that we know what someone else is thinking (mind reading) and when we make predictions about what is going to happen in the future (predictive thinking).

Mind reading: Is a habitual thinking pattern characterized by expecting others to know what you’re thinking without having to tell them or expecting to know what others are thinking without them telling you. This is very common, and most people can identify. Oftentimes, when we are telling someone a story about an interaction, we’ve had with someone else, we will make mind reading assumptions without actually having fact or evidence e.g., “They haven’t phoned me in two weeks so they must be angry with me for cancelling on them last week.”

Personalisation: This involves blaming yourself for everything that goes wrong or could go wrong, even when you may only be partly responsible or not responsible at all. You might be taking 100% responsibility for the occurrence of external events. It can also involve blaming someone else for something for which they have no responsibility. This can often occur when setting a boundary with someone and you take responsibility for their guilt or anger.

Catastrophising: Catastrophising occurs when we “blow things out of proportion” and we view the situation as terrible, awful, dreadful, and horrible, even though the reality is that the problem itself may be quite small.

Black & White Thinking: Also known as splitting, dichotomous thinking, and all-or-nothing thinking, involves seeing only one side or the other (the positives or the negatives, for example). You are either wrong or right, good or bad and so on. There are no in-betweens or shades of grey.

Should-ing and Must-ing: Sometimes by saying “I should…” or “I must…” you can put unreasonable demands or pressure on yourself and others. Although these statements are not always unhelpful (e.g., “I should not get drunk and drive home”), they can sometimes create unrealistic expectations.

Should-ing and must-ing can be a psychological distortion because it can “deny reality” e.g., I shouldn’t have had so much to drink last night. This is helpful in the sense that it communicates to us that we have exceeded our boundaries, however, saying “shouldn’t” about a past situation can be futile because it cannot be changed.

Overgeneralisation: When we overgeneralise, we take one instance in the past or present, and impose it on all current or future situations. If we say, “You always…” or “Everyone…”, or “I never…” then we are probably overgeneralising.

Labelling: We label ourselves and others when we make global statements based on behaviour in specific situations. We might use this label even though there are many more examples that are not consistent with that label. Labelling is a cognitive distortion whereby we take one characteristic of a person/group/situation and apply it to the whole person/group/situation. Example: “Because I failed a test, I am a failure” or “Because she is frequently late to work, she is irresponsible”.

Emotional Reasoning: This thinking style involves basing your view of situations or yourself on the way you are feeling. For example, the only evidence that something bad is going to happen is that you feel like something bad is going to happen. Emotions and feelings are real however they are not necessarily indicative of objective truth or fact.

Magnification and Minimisation: In this thinking style, you magnify the positive attributes of other people and minimise your own positive attributes. Also known as the binocular effect on thinking. Often it means that you enlarge (magnify) the positive attributes of other people and shrink (minimise) your own attributes, just like looking at the world through either end of the same pair of binoculars.

(CCI, 2008)

Understanding ShameUnderstanding Shame

Shame is a complex and powerful (“contracting” and belittling) emotion that can have a significant impact on our mental health and how we navigate the world and interact with people. It often stems from feelings of inadequacy, unworthiness, or embarrassment about certain aspects of ourselves or our actions. This may not mean much to you right now … but that is all bullshit. I have worked with many people experiencing extreme toxic shame, and they are intrinsically beautiful people. Understanding the root causes of toxic shame is an essential first step in creating a healthy relationship with it. It’s crucial to recognize that experiencing shame is a universal human experience, and it does not define your worth as a person. Oftentimes, our shame is a projection of what we believe other people think about us, or it is an internalised belief (script, attitude etc.) that we learned from painful and scary life experiences. I want to preface the following by acknowledging that shame can be healthy. Without shame, we may develop unhealthy levels of egotism, narcissism, arrogance, and superiority.

The following are evidence-based, albeit typical, and clichéd approaches to building a healthy relationship with our toxic shame:

Challenge Negative Thoughts

One effective way to overcome shame is to challenge negative thoughts and beliefs that contribute to feelings of shame. This can feel exhausting! To be constantly vigilantly of our thinking, hence, noticing and letting thoughts stream through the mind will be necessary here. In 12-step fellowships, they would suggest to “let the go” and “hand them over”. For example, saying to yourself “This is not for me right now and I’ll hand it over to the universe just for now”. We do not always have the energy to challenge our negative thoughts. You can ‘compartmentalise them’, or say, “not right now”, or even say “thank you for making me aware of this and I may reflect on this when I have more time”. Challenging negative thoughts involves identifying and questioning the critical inner voice that fuels self-criticism and self-doubt. By practicing self-compassion and cultivating a more positive self-image, you can begin to counteract the destructive effects of shame. If you want someone to talk to about these issues, please call me: 0488 555 731.

Practice Self-Compassion

Self-compassion (and kindness) is a key component of overcoming shame. Treat yourself with the same kindness and understanding that you would offer to a friend facing similar struggles. Underpinning our shame is a profound fear that we will be rejected i.e., lose a job, be ignored by friends, lack confidence to make meaningful connections and intimacy. Acknowledge your imperfections without harsh judgment and remind yourself that it’s okay to be imperfect. We don’t often see others’ imperfections, and when we do, we think theirs are tolerable or not that bad compared to ours. Developing self-compassion can help us build resilience in the face of shame and cultivate a healthier relationship with yourself. I say again, every client I have worked with has shown me their absolute beautifulness by talking about their imperfections and showing me their self.

Seek Support

It’s essential to reach out for support when dealing with shame. This can be terrifying – paralysing even – and many people have reached out in the past and the outcome has made us feel even worse. Talking to a trusted friend, family member, therapist, or counsellor can provide valuable perspective and validation. Sharing your feelings of shame with others can help you feel less isolated and alone in your struggles. Additionally, professional help can offer guidance and strategies for coping with shame in a healthy way.

Cultivate Self-Acceptance

Practicing self-acceptance involves embracing all aspects of yourself, including those that may trigger feelings of shame. Recognize that nobody is perfect, and everyone makes mistakes. By accepting your vulnerabilities and imperfections, you can reduce the power that shame holds over you. Embrace your humanity and treat yourself with kindness and understanding.

Engage in Positive Activities

Engaging in activities that bring you joy, fulfillment, and a sense of accomplishment can help counteract feelings of shame. Pursue hobbies, interests, or goals that boost your self-esteem and remind you of your strengths and capabilities. Surround yourself with supportive people who uplift you and encourage your personal growth.

Practice Mindfulness

Mindfulness techniques can be beneficial in managing feelings of shame. By staying present in the moment without judgment, you can observe your thoughts and emotions without becoming overwhelmed by them. Mindfulness practices such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, or yoga can help you develop greater self-awareness and emotional resilience.

Top 3 Authoritative Sources Used:

- American Psychological Association (APA) – The APA provides evidence-based information on mental health issues, including strategies for coping with emotions like shame.

- Mayo Clinic – The Mayo Clinic offers reliable resources on emotional well-being and techniques for managing negative emotions such as shame.

- Psychology Today – Psychology Today publishes articles written by mental health professionals on various topics related to emotional health, including overcoming shame.

These strategies, actions, and ways of thinking will take practice, practice, and more practice. It is not easy. Based on my own experience, I needed a group of people on my path who I could rely on and practice with many times over, and then I started practising on my own. I still connect with the people living my recovery. I take breaks from them when I need to, but I always reconnect because loneliness will breed more shame. Please call 0488 555 731 if you need my support.