Considering counselling? Located Sydney City area: Surry Hills

Related Post

Cognitive (thinking) ErrorsCognitive (thinking) Errors

Well, hello and good morning, afternoon, and evening readers. I truly hope you’re swimming in the pleasantries of life rather than keeping your head above water in the unpleasant swamp. HOPE = Hold On Pain Ends. And there’s generally a learning or personal growth that comes after the storm of every painful experience, even if it’s simply greater empathy and compassion for others.

Today’s the day to learn or remember the fallacies of the human mind. I am not as smart as I look, haha. Have you heard of heuristics before? In cognitive psychology, a heuristic is a mental “shortcut” that allows people to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. They can be very helpful in many situations, but they can also lead to cognitive biases, errors in thinking, and even perhaps without the mental shortcut, our thinking is often filled to the brim with cognitive distortions, assumptions and fallacies (faults). Awareness raising is probably the first step to identify our own cognitive traps and also identify them in others. Cognitive errors are natural – we all have them. Below are some cognitive distortions/errors to be aware of when we reflect on our interactions with people, during personal reflection, and when making meaningful decisions or judgements.

- ALL-OR-NOTHING THINKING (aka. POLARISED THINKING, SPLITTING, and BLACK-AND-WHITE THINKING: is extreme thinking i.e., the error in a person’s thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both positive and negative qualities of the self and others into a cohesive, realistic whole. It is a common defense mechanism. Before you think “I must have really shitty thinking because I do this ALL the time”, give yourself a break. If you’re thinking in black and white, you probably internalised this from social media, television and movies, your family of origin and the broader society. Be mindful of using extreme, dichotomist terms, such as “failure”, “success”, “best”, “worst”, “freezing”, “boiling”, “everything”, and “nothing”. If you think “I’m a terrible person”, that is bullshit and inaccurate. You may have behaved terribly for a period of time towards yourself, to someone else, or towards some “thing”, but we cannot discount all the NON-terrible qualities about you. We must THINK in DIALECTICS i.e., the ability to view issues from multiple perspectives with reason and wisdom or in other words being able to have two contradictory viewpoints, where a greater truth emerges from their interplay. The truth is, if you think you’re a terrible person, there’s also virtuous person in there too.

- OVERGENERALISTION: The words “always”, “every” and “never” come into play here, and you have an unshakable “rule” or “conviction” about yourself, something, or someone, based on one or two incidences. Overgeneralising is “a cognitive distortion in which an individual views a single event as an invariable RULE, so that, for example, failure at accomplishing one task will predict an endless pattern of defeat in all tasks.” Coming into the present moment and being specific can be helpful if you are someone who overgeneralises. You may also want to ask yourself if what your saying is the really the truth. Is it really accurate or correct. There’s an assumption that because something has happened once or a few times that it’s like going to happen every time. Remember, the words “always”, “every”, and “never” frequently appear in this cognitive “trap”. I encourage you to look at the big picture and ask yourself if what you’re saying or thinking is accurate. Overgeneralisations tend to be vague and board statements e.g., “I always get every red light”. Perhaps this is part of our evolutionary negativity bias. We tend to notice the so-called “bad” and overlook the so-called “good”. If you find yourself using overgeneralisations that suggest a future prediction (e.g., “I’ll never get a partner) … use some humour – you may have big balls but neither one of them are crystal – VEEP. If there is some truth to unusually frequent and specific situations that are making your life unpleasant, validate them, talk to someone, and brainstorm some solutions. We humans have plenty of blind spots that others can see sometimes.

- MENTAL FILTER: is considered to be the opposite to OVERGENERALISATION the mental filter takes one small event and focuses on it exclusively, filtering out anything else that’s relevant. Filtering out the positive and focusing on the negative can have a detrimental impact on your mental well-being. Filtering out the so-called “negative” can also make one a bit hubris (excessive pride or self-confidence), arrogant, vain and conceited – and then you’re just a stone’s throw away from narcissism.

- PERSONALISATION AND BLAME: Personalization and blame is a cognitive distortion whereby you entirely blame yourself, or someone else, for a situation that in reality involved many factors that were out of your control. I think this is a symptom of our wounded ego, or simply just the ego. As human’s we are egocentric, like children, and we often think that circumstances in our environment are solely because of our influence. For example, your friend isn’t behaving like they usually do, so it must be because you have done something.

Again, personalisation is an egocentric error in cognition. “Of course it has to do with me”, we think. It makes sense that we personalise things. We are the star of our own show, our own narrative. If you personalise something, it means we’ve directly influenced it – we are the primary cause. This may elicit internal pain, shame or guilt, so what’s the pay-off? Personalisation is a cognitive error that offers us the illusion of control e.g., “If we caused it then we will learn how to not cause it again, and maybe even undo what we have caused”. If you think about it, personalising something is something children do. Remember, there are infinite variables in any situation to take full credit of the outcome. That being said, it is responsible and mature to reflect objectively on the influence of our behaviour and what we can learn about our shortcomings.

Blame deserves it’s own blog post but in short, it can be defined as a defence mechanism to protect the self from feeling some unwanted emotion or thinking something unacceptable in relation to the “self”. Blaming provides a way of devaluing others, an the pay-off or reinforcement the blamer receives is a sense of superiority. It protects our ego from feeling responsible for something, and protects us from feeling guilt or shame. Perfectionists are very good at blaming others, and themselves. Even if you genuinely think faulting someone or something is valid, remember that no one is perfect. Recognise that you are human and others are fallible humans. As they say in recovery, “there is a bit of bad in the best of us and a bit of good in the worst of us“. We may have internalised from society and culture that we couldn’t make mistakes (because we receive “punishment” for making mistakes) but we must move beyond that now. As adults, we need to get real. Validate your experience because it may be very disappointing when we don’t meet others or our own expectations. We must nurture and care for the wounded child. Lets attend and befriend to our shortcomings and accept we are not superhuman. Learn to expect you will make mistakes. Failure is kind of an illusion, isn’t it? Or maybe a social construct? “Failure” is really learning – replace ‘failure’ with the word ‘feedback’. Would a cat or dog blame them self for a “mistake”? In the minds of animals, there’s no such concept as failure or a mistake.

Here’s a link to website “simplypsychology” that discusses a theory called Attribution Theory, an idea about how people explain the causes of behaviour and events: Attribution Theory – Situational vs Dispositional | Simply Psychology

Three rules for identifying abnormal child sexual behavioursThree rules for identifying abnormal child sexual behaviours

Retrieved and edited 06/12/2021 from “Voice of Experience: Three rules for identifying abnormal child sexual behaviors” by Gregory K. Moffatt, a veteran counsellor with more than 30 years experience. If you are a survivor of sexual trauma at any age, I encourage you not to read this article.

From the perspective of Moffatt’s professional experience, childhood sexual behaviours can be grouped into three categories: 1. normal behaviours, 2. behaviours that are not normal but not unusual, and 3. behaviours that are abnormal or statistically rare. For the purpose of this post, I will be replacing the word “normal” with “natural” and/or “common” moving forward.

Rule No. 1: Natural or common sexual behaviours in children are never forced. The exploration is mutual. While one child likely had the idea first, both children must participate freely. This doesn’t mean that two children might willingly agree to engage in abnormal sexual behaviours, however, therefore read the next to rules for clarification.

Rule No. 2: Natural or common sexual behaviours in children are never painful. Children who behave within cultural and developmental norms will stop what they are doing when they realise they have caused pain.

Rule No. 3: Natural or common sexual behaviour in children is never invasive. Natural childhood curiosity does not include inserting objects or one’s own body parts into the cavities of others — anus, vagina, mouth, etc.

I’m unsure why Moffatt didn’t make this a 4th rule – he did add that most of the time, this type of childhood behaviour occurs between children of similar age. It is highly unusual for a young child to sexually engage with a teen without violating one of the three rules above. That behaviour definitely calls for further investigation. And, certainly, any sexual interaction between an adult and a child is cause for mandated reporting.

When our intelligent and necessary emotion – ANGER – becomes unhealthy and damagingWhen our intelligent and necessary emotion – ANGER – becomes unhealthy and damaging

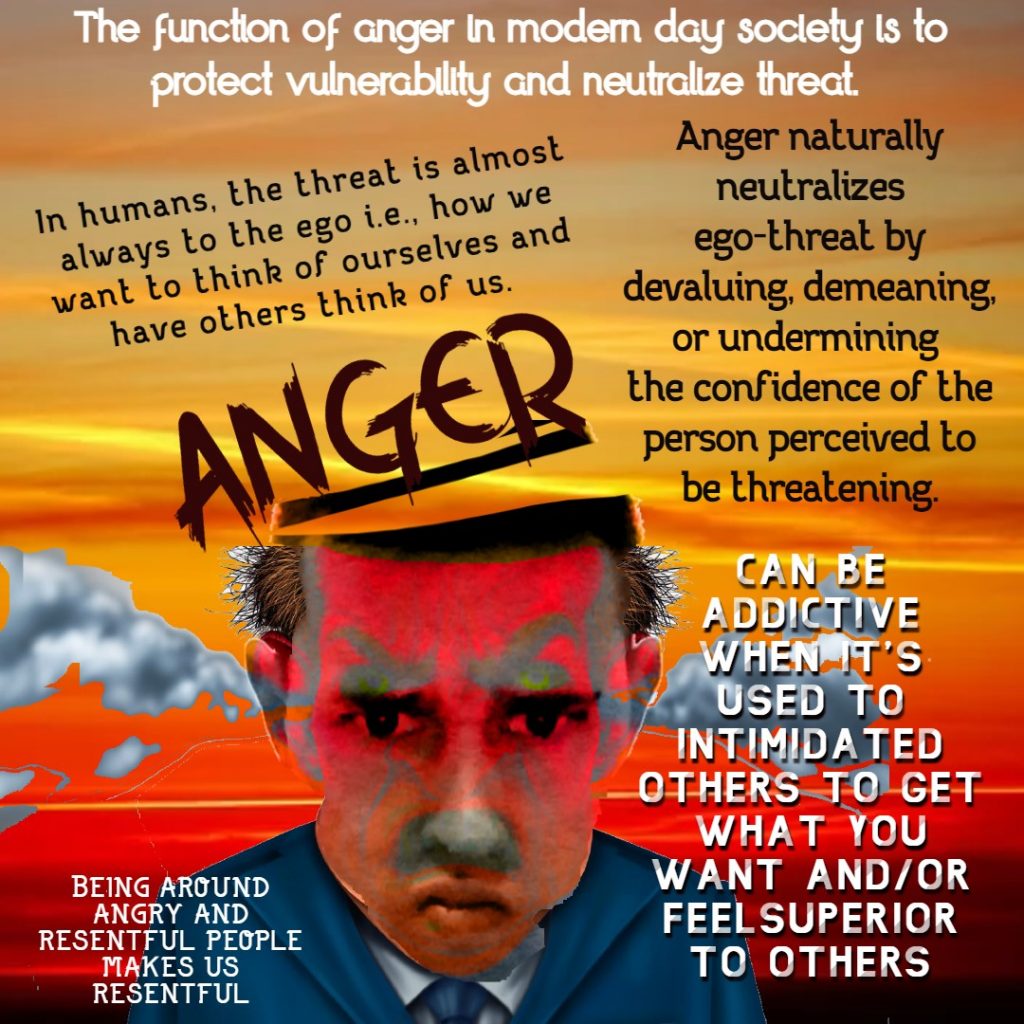

The function of anger is to protect vulnerability and neutralize threat.

The threat humans cognitively perceive is almost always to the ego i.e., how we want to think of ourselves and have others think of us. Anger neutralizes ego-threat by devaluing, demeaning, or undermining the “power” of the person perceived to be threatening. Humans get angry when they don’t get what they want, when they’re disrespected, or when they perceive something is unjust/unfair. Anger, the emotion, is a chemical messenger. It communicates to us, to others, and motivates us to act, speak, do something. Healthy responses to anger include being assertive, feeling empowered, protecting ourselves and love ones from ACTUAL threat, setting boundaries with others, and making social change for justice (for example). It becomes unhealthy when we become passive-aggressive, violent, vengeful, spiteful, aggressive, resentful, sarcastic, “moody”, rude etc.

Receive the message and respond from a wise, calm place after the intensity of the emotion has past. Sometimes we have to act in the moment. Our ancestors may have required this for fight/flight survival. These days, we can generally PAUSE and calm the self before responding from a mindful and compassionate heart and mind. Remember: Hurt people, hurt people.