Psychological factors influencing drug use in Sydney’s gay community often stem from unique social and emotional challenges. Research highlights that stigma, discrimination, self-stigma, and internalised homophobia can lead to feelings of isolation, shame, and mental distress, which may increase vulnerability to substance use.

Additionally, the normalisation of partying in certain social settings, such as bars and clubs, has historically been a way for subcultural populations of LGBTQ+ individuals to connect and find community. However, this environment can also contribute to higher rates of drug use. Emotional coping mechanisms, such as using substances to manage stress or trauma, are also significant factors.

The biopsychosocial model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding alcohol and other drug dependency in the LGBTIA+ community. Here’s a breakdown of the factors:

- Biological Factors:

- Genetic predisposition plays a role, with some individuals being more vulnerable to chemical dependency due to inherited traits.

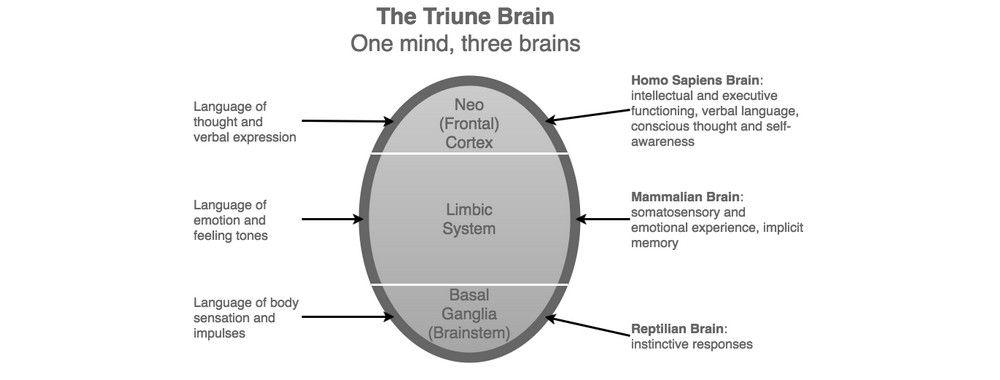

- Neurobiological changes caused by substance use can alter brain function, making it very challenging to reduce or stop using substances despite the negative consequences occurring in the individual’s life.

- Psychological Factors:

- Trauma, such as adverse childhood experiences, peer bullying, neglect, authoritarian child rearing, seemingly innocuous societal messages, and/or discrimination, can lead to emotional distress and substance use as a coping mechanism.

- Internalised stigma, homophobia, or transphobia can exacerbate mental health issues like anxiety and depression, increasing the risk of substance use and potential physical and psychological dependency.

- Social Factors:

- Experiences of ostracism, violence, or lack of acceptance and belonging can lead to isolation and substance use.

- Social norms in certain LGBTQ+ spaces, such as bars or clubs, may normalise or encourage substance use.

This model underscores the importance of addressing all these interconnected factors in prevention and treatment efforts.

The Flux Study, also known as “Following Lives Undergoing Change,” is a longitudinal research project focusing on the lives of gay and bisexual men in Australia. Conducted by the Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney, it examines various aspects of health, behaviour, and social factors, including drug use, sexual health, and the adoption of HIV prevention strategies like PrEP.

Key findings from the study include:

- Recreational drug use is common among gay and bisexual men, with substances like marijuana, amyl nitrite (“poppers”), and party drugs being frequently used. However, dependency rates are relatively low.

- Drug use is often linked to enhancing pleasurable experiences, including sexual enjoyment.

- The study has provided insights into how men mitigate risks, such as using biomedical HIV prevention methods alongside drug use.

The Flux Study is a collaborative effort involving organisations like the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, ACON, and the Victorian AIDS Council. It aims to inform health interventions and support services tailored to the needs of this community.

The Flux Study has provided valuable insights into the health and behaviours of gay and bisexual men in Australia. Here are some key findings:

- Drug Use: While recreational drug use is common, most participants reported infrequent use. Harm reduction strategies, such as not sharing injecting equipment, were widely practiced.

- HIV Prevention: There was a significant increase in the uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), with usage rising from less than 1% in 2014 to about one-third of participants by 2017.

- COVID-19 Impact: During the pandemic, participants reduced sexual contacts and adapted strategies to minimize risks in sexual contexts. Many also paused PrEP usage due to reduced sexual activity.

- Mental Health: A notable proportion of participants reported mental health challenges, highlighting the need for targeted support services.

There are several support services available for addressing mental health challenges, particularly for the LGBTIA+ community in Australia. Here are some key options:

- QLife: A free, anonymous peer support and referral service for LGBTQ+ individuals. It operates via phone and webchat from 3 PM to midnight, 7 days a week. Phone: 1800 184 527. Their website provides a webchat service: QLife – Support and Referrals

- Beyond Blue: Offers 24/7 mental health support, including phone and online counselling. They also provide resources tailored to the LGBTQ+ community. Phone: 1300 22 4636. Click the following link to Beyond Blue’s Wellbeing Action Tool: beyond-blue-wellbeing-action-tool_dec_2024_updated.pdf

- Lifeline: A leading crisis support service available 24/7 for anyone in distress. They offer phone, text, and online counselling. Phone: 13 11 14

- Head to Health: Connects individuals to mental health resources, including helplines, apps, and digital programs. Medicare Mental Health is a free service that connects you with the mental health support that is right for you. Phone: 1800 595 212 or visit their website: Home | Medicare Mental Health

- WayAhead Directory: An online database to find local mental health services and resources. Phone: 1300 794 991

- NSW Mental Health Line: A 24/7 telephone service providing advice and recommendations for appropriate care. Phone: 1800 011 511

These services are designed to provide immediate support and guide individuals toward long-term mental health care.