Not long ago, words like “triggered,” “gaslighting,” “narcissist,” and “neurodivergent” belonged almost exclusively to therapists’ offices and psychology textbooks. Now they’re everywhere; in workplace training sessions, community organisations, TikTok comment sections, and casual conversation between friends over coffee. That shift has brought some genuinely important changes. But it’s also introduced some problems worth taking seriously.

The real wins

It would be unfair to dismiss this cultural shift outright. There are meaningful gains. More people today can identify manipulation, coercive dynamics, and emotional harm than any previous generation. Mental health conversations have been destigmatised in ways that would have been hard to imagine twenty years ago. People who were historically silenced, particularly those from marginalised communities, finally have language that validates their experiences and gives them permission to leave harmful situations. That’s progress

But then there’s “concept creep” (pathologising the ordinary or “diagnostic inflation”)

Psychologists use the term “concept creep” to describe what happens when a word originally defined by strict clinical boundaries starts expanding to cover increasingly ordinary experiences. And that’s precisely what happened with “trauma.”

Clinically, trauma refers to experiences that overwhelm the nervous system i.e., genuine threats to safety, severe harm, events that exceed a person’s capacity to cope. These days, the same word is regularly applied to being disagreed with, having a relationship end, receiving criticism, or simply feeling uncomfortable. Events like relationship breakdowns, job loss, or failure can be genuinely devastating, and for some people, under some circumstances, they absolutely do meet the clinical threshold for trauma. The distinction isn’t really about the type of event. It’s about the impact on the nervous system and the person’s capacity to integrate the experience.

When everything qualifies as trauma, the word stops doing useful work. Worse, it can actually undermine the resilience people need to navigate a genuinely difficult world.

The nervous system problem

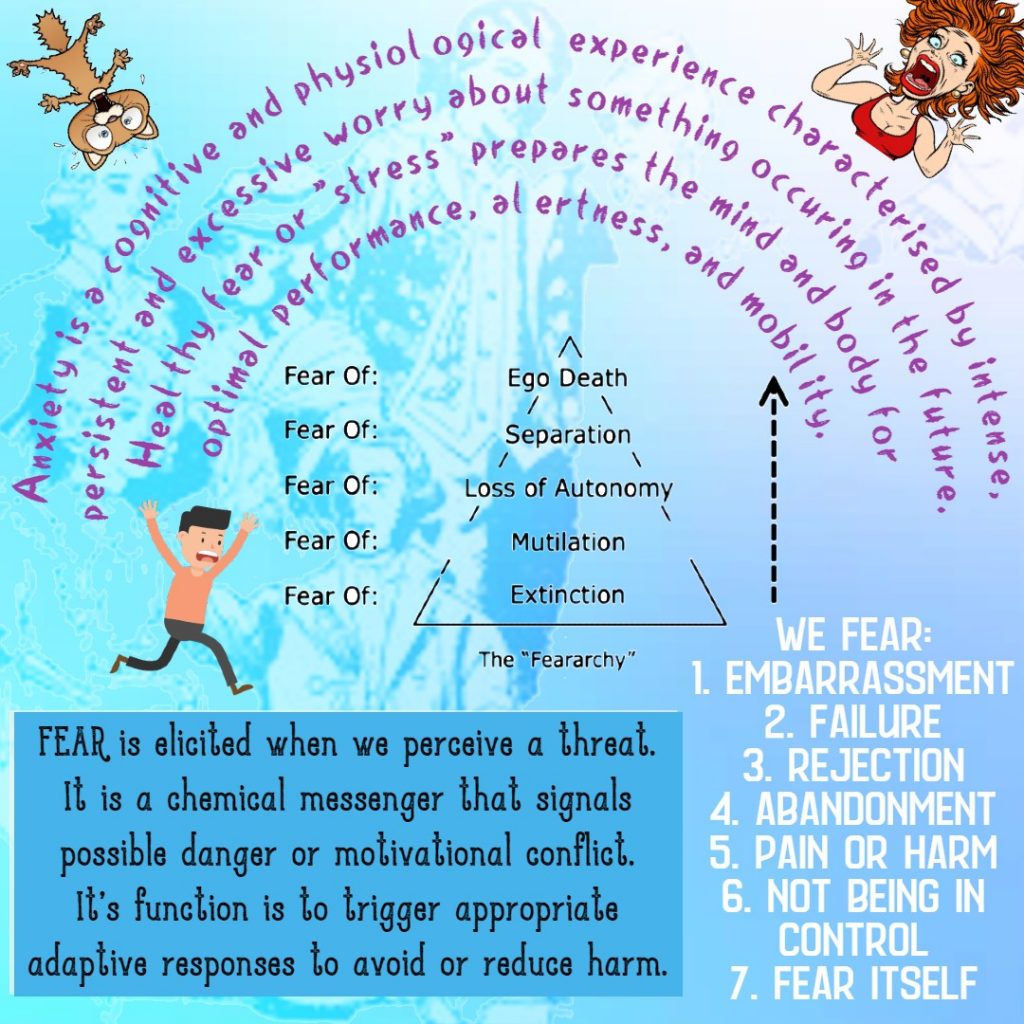

Here’s where it gets important. In actual “clinical” trauma, the brain’s threat-response systems activate intensely. Memory processing is disrupted. The body mobilises for survival in ways that can leave lasting marks.

Discomfort is different. It involves real emotional activation, it’s not pleasant, but cognitive flexibility remains available. The capacity to think, reflect, and choose a response is still intact.

When people learn to label ordinary emotional discomfort as trauma activation, the consequences compound. If discomfort feels equivalent to harm, avoidance becomes a logical response. But avoidance prevents the gradual building of tolerance. And without tolerance, the world gets smaller.

Trauma as identity and social currency

In some online communities, there’s an uncomfortable dynamic worth naming: being “highly traumatised,” “chronically triggered,” or “deeply misunderstood” can confer real social benefits — belonging, validation, moral authority, and attention.

This doesn’t mean the experiences aren’t real. But when distress becomes central to someone’s identity, letting go of that distress can start to feel like losing themselves. Recovery, paradoxically, becomes threatening.

The fragility trap

In certain environments, fragility functions as a kind of protection. If I am highly sensitive, others must accommodate me. Challenge becomes inappropriate. Accountability becomes unsafe. The person is shielded, but the cost is enormous.

Resilience, both psychologically and biologically, develops through graded exposure to stress. We become capable through encountering difficulty, not by avoiding it. Systems that never face adaptive pressure weaken over time. This is simply how human development works.

Why this moment matters

Several things are converging right now. Social media algorithms reward extreme emotional narratives. Identity formation increasingly happens in digital spaces that amplify distress. Institutions have frequently overcorrected towards protective language in ways that, whatever their intentions, can inadvertently signal that discomfort is dangerous. And while there’s been important growth in awareness of systemic injustice, the corresponding emphasis on individual agency has sometimes been lost.

We’ve swung from “suppress your emotions entirely” to “your emotions define reality.” Neither extreme serves people well.

Holding the middle ground

What good support actually looks like isn’t dismissing people’s experiences, it’s deepening them. The distinction that matters is between trauma-informed practice and what might be called trauma-indulgent practice.

Trauma-informed means understanding that harm genuinely impacts nervous systems, avoiding shame, recognising power imbalances, and creating safety. It’s grounded and necessary.

Trauma-indulgent means treating all discomfort as harm, reinforcing avoidance, allowing emotional reasoning to override reality, and quietly removing personal responsibility from the picture. It feels compassionate in the moment but tends to leave people worse off over time.

In practice, holding the middle ground means validating what someone feels while gently asking whether something was truly unsafe or simply hard. It means acknowledging difficulty while also reinforcing capacity. It means introducing a reality that doesn’t get much airtime in online spaces — that we can’t always control how those around us speak or behave, but we can build our own tolerance and capacity to regulate.

The question underneath everything

There’s a deeper ethical question running through all of this: are we reducing suffering in the long run, or just distress in the short term?

Protecting people from discomfort today, if it increases fragility tomorrow, is not a kindness. But exposing people to challenge without adequate safety and support risks re-traumatising those with genuine wounds.

The balance isn’t complicated to describe, even if it’s genuinely difficult to hold: safety, combined with graduated exposure, combined with a genuine sense of agency.

Anyone supporting others through difficulty needs a calm nervous system, a high personal tolerance for distress, and the capacity to sit with being perceived as insensitive when holding a difficult but necessary line. Clear values and genuine boundaries aren’t optional extras — they’re the model.

The world remains economically uncertain, socially polarised, and digitally relentless. People will encounter disagreement, rejection, imperfect institutions, and others who handle things badly. Preparing people for a world where everyone is perfectly considerate is not just unrealistic — it’s a disservice.